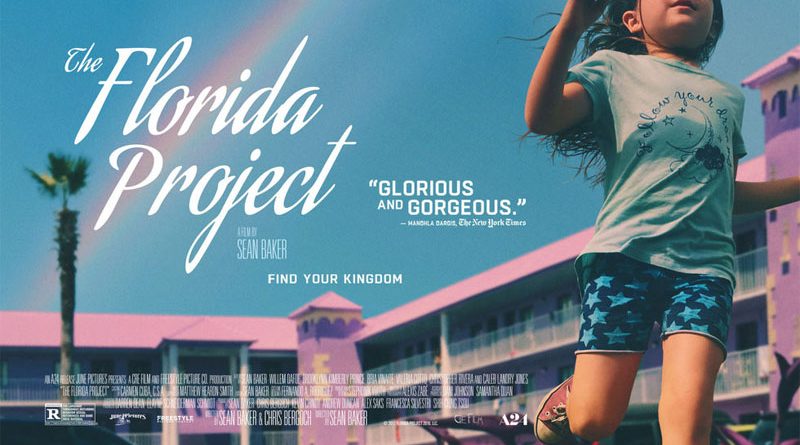

Upon observing how the housing crisis took its toll, Baker took a journalistic approach in researching his film. He interviewed residents, motel managers, and social services in order to craft a holistically authentic representation. The tale unfolded after discovering Route 192 and its Magic Castle motel, a pastel purple slum in which the film’s six-year old Moonee and her friends live. Along this route are gaudy, Disney knock-off tourist traps that reinforce the childlike nostalgia Baker sought after. The story was shot and set over the course of one summer—the summer where Moonee’s innocence is threatened by her mother’s circumstances. For the exception of Willem Dafoe, Baker selected fresh faces with no acting experience not only to keep the audience immersed in realism but also to ensure the actor’s performances were as genuine as possible. The cast’s wardrobe was selected from local thrift stores where residents of these motels shop. The Magic Castle stayed open for business while shooting, and the extras are mostly residents who agreed to be a part of Baker’s project. According to our textbook, “Realism for Bazin is not so much a style that one can apply or an effect induced in the spectator, but rather an attitude or stance that the filmmaker adopts vis-à-vis the world he encounters…” (Elsaesser and Hagener 30). In “The Evolution of Film Language”, Andre Bazin believed there are two types of directors: “those…who put their faith in the image and those who put their faith in reality.” Baker is the latter, shooting on 35mm with classically composed, widescreen shots that lend beautifully to the lush and swampy aesthetic of central Florida. Shooting from the child’s perspective provides us with vivid pops of color and heightened magic reflecting how these children interpret their surroundings. Although it is an atypical portrayal of poverty, it becomes as true to us as our own vivid nostalgia of childhood.

After Moonee’s mother, Halley, gets caught having male visitors over to pay her rent, the film toggles from the climactic trouble brewing in reality, to Moonee and her friend, Jancey, oblivious to what is at stake within the drama of the adult world. The sequence begins with Halley and motel manager Bobby arguing after his newly imposed rules to keep Halley from having clients in her motel room. A young mother covered in tattoos with faded teal hair, she regresses into a child herself frequently and especially here as she whines to Bobby, “You’re not my fucking father.” Moonee lurks behind, slowly becoming aware that something is wrong in her mother’s sphere. A stand-off between Bobby and Halley result in him “counting ‘til three” while she pushes him to his last nerve. A slap of her maxi-pad on the window ends this scene, and we cut immediately to Moonee and Jancey huddled beneath a mossy oak tree, caught in an afternoon storm. As summer rain showers are frequent in Florida, Baker did not have to wait long to capture this scene whose setting was selected due to its impressive tree. Once the storm subsides, the low camera follows as the girls walk hand-in-hand to a pasture with cows grazing. We feel like we are one of the gang with these children, trailing Moonee close behind. The cows become the girls’ own safari; and just as small children are inclined to pretend, Moonee and Jancey make-believe Disney since they cannot have the actual experience. Imagination influences and drives their lives to compensate for what they are lacking.

Cut back to the Magic Castle. Halley smokes a cigarette, waiting for her laundry to finish while Moonee plays with her toys. Again, there is a juxtaposition of reality and fantasy, of the frightening adult world threatening the virtues of youth and its freedom from substantial worry. Perched atop a washing machine and scrolling on her phone, Halley is snubbed by a resident due to her new reputation as a whore. With Moonee on the curb, the danger is creeping closer into her space. The next scenes are comprised of Halley asking her former best friend, Ashley, to spot her rent since she’s no longer able to keep up the hustle. Ashley calls her out with an internet ad, and Halley shamelessly denies her own picture before her like a stubborn child. Upon being threatened, Halley proceeds to jump Ashley and brutalizes her while her son, Scooty, witnesses the entire confrontation. This pivotal moment demarcates the story as it swiftly ends the separation between a child’s naivety and the tumultuous adult affairs.

With the arrival of sound, the cinema began to move into realism. This film realistically represents the environment in which it is set, and there is no soundtrack or non-diegetic sound to take away from what takes place on screen. As per our text, “the window offers a detail of a larger whole in which the elements appear as if distributed in no particular way, so that the impression of realism for the spectator is above all a function of transparency” (Elsaesser and Hagener 18). Halley would have been a teen mom with Moonee, and thus the lack of maturity Halley has is appropriate considering she is raising a child alone. She is maladjusted to the working-class world, having been recently fired from a strip club. The local diner wouldn’t hire her either, but to Moonee she is the world. And rightfully so, as Halley loves Moonee with all of her heart regardless of not knowing how to be a parent or role model.

The complexity of this relationship accurately depicts a range of rights and wrongs, good and bad, asserting a spectrum on which humans exist. A spectrum the audience misses in most classical cinema and blockbusters. These multi-faceted characters represent actual people who are figuring it out as they go. There are no patterns of narrative development. The exposition of the adult world is often traded for the vignettes of its children. Baker carefully ensures his audience stays in the moment of the child because that is our only hope at redeeming this story. We don’t get the luxury of a happy ending or a resolution wrapped-up with a neat bow. We aren’t awarded those things because that is not how life operates. The ending is left ambiguous, so we must question and speculate to fill in our own fantasy of where this story continues.

Works Cited

Bazin, André (2010). The evolution of the language of cinema. In Marc Furstenau (ed.),

The Film Theory Reader: Debates and Arguments. Routledge.

Elsaesser, Thomas, and Malte Hagener. Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses. Routledge, 2015.

Santich, Kate. “Thousands of Motel-Living Families Face Shaky Future.”

OrlandoSentinel.com, 8 Oct. 2015, www.orlandosentinel.com/news/local/oshomeless-families-motels-20151005-story.html.

“The Florida Project – Sean Baker, Chris Bergoch, and Alexis Zabe Q&A.” YouTube, 10Oct. 2017, youtu.be/qo6Jg7UxLfY.

Leave a comment